Southeast Asian countries engage in a variety of intra-regional and extra-regional energy trade flows, from Indonesian coal exports to China, to the Yadana-Ratchaburi gas pipeline linking Myanmar and Thailand, to Malaysian oil field exports to Japan. One of the more dynamic areas of energy trade occurs in the Greater Mekong Subregion (Cambodia, China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam) in the form of cross-border hydroelectricity sales.

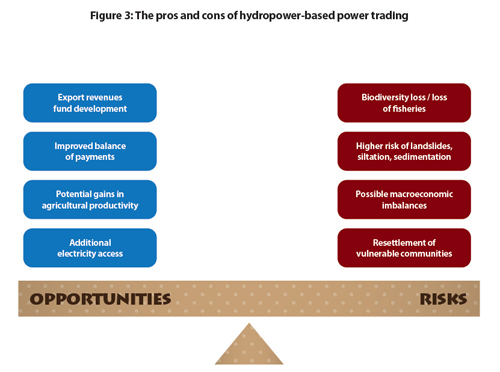

Given the abundant and relatively undeveloped hydropower potential of the region, cross-border trade has emerged as a cost-effective means of expanding energy access. While commanding a strong list of motivating factors, hydropower development has its share of detractors. Downstream impacts, disrupted livelihoods, and the potential loss of endangered species are common criticisms, though dam backers believe these risks can be mitigated and affected parties given sufficient compensation.

Towards a GMS Power Trading scheme

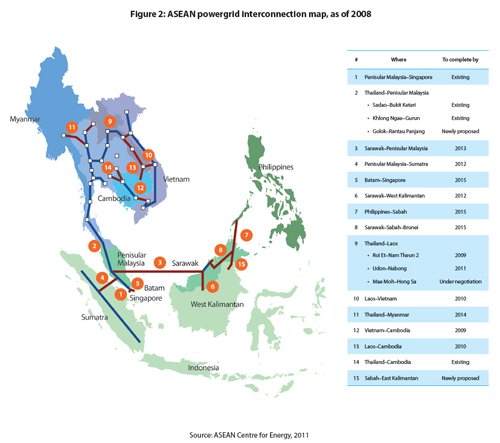

Though the current status of power trading in the region is a patchwork of bilateral contracts, heads of state and power industry leaders from the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) countries have been actively working to realise the ambitions of the GMS Power Trading scheme. Under this Asian Development Bank-supported project, power generation plants will become connected through a regional network of cross-border interconnections and wholly competitive buying and selling markets. The GMS network will then compose one of the three ASEAN Power Grid (APG) subsystems which will integrate all ten ASEAN countries by 2015, via fifteen overland and subsea interconnections. The current face of power trading may be predominantly hydroelectric in nature, but the future will see greater diversification when the APG connects to nuclear and thermal generation plants.

But what, if anything, does this mean for the poor

Drivers and motivations of power trading

The economic justification for power trading is multifaceted and compelling in its own right. Countries with low-generating reserve margins and growing electricity demand may find that importing electricity from neighbouring countries with excess capacity may be more cost-effective than building new capacity. This rationale is even stronger when private capital cannot be attracted because of anticipated low rates of return, or because influential environmental lobbies have captured the policy process.1

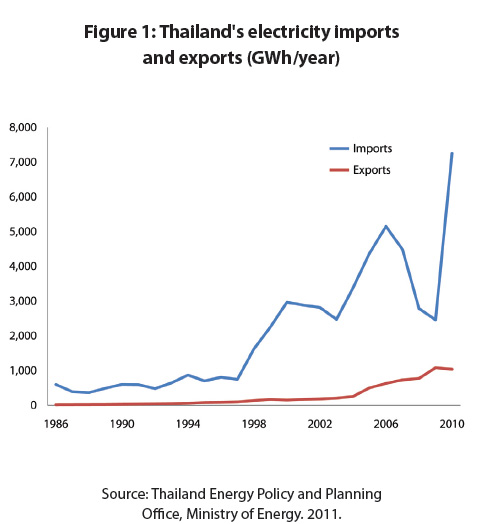

Both of these reasons apply to Thailand which imports a small, but growing percentage of its electricity from Laos, whose hydropower potential exceeds 20,000MW, but whose national demand is under 400MW.2 When such trading agreements are formed, relationships often become bi-directional because of seasonality or geography. Laos imports electricity during the dry season when its reservoir levels are low, and in border areas where domestic transmission infrastructure is lacking, which totalled US$50 million in 2010.3

In some cases, the local customer base is too small to justify infrastructure investment. However, adding foreign customers (commercial and residential) to the deal may achieve financial viability. And as with exports of other goods and services, exporting countries enjoy an improved balance of payments as well as royalties and/or taxes on natural resources that may otherwise not be accessed.

The energy security implications of power trading, however, are less clear-cut. On one hand, regional spot market trading offers greater flexibility in responding to dynamic demand levels, but these gains need to be weighed against other losses in versatility. As Professor Peter Hartley at Rice University's James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy notes, "If your gas supply gets cut off, you can make electricity in other ways. But if you are importing electricity and that gets cut off, you have blackouts."4

Vietnam faces a similar situation, since it resolves its domestic shortfall with imports from China. While Electricity of Vietnam, the state-owned utility, has been continuously receiving electricity from the Chinese supplier, the contract terms have yet to be agreed upon and as of March the supplier has threatened a 15 percent price increase.5 Though Chinese imports account for only 4 percent of Vietnam's total electricity demand, it is a necessary contribution in a country that continues experiencing supply shortages. The contrary applies to Thailand, where electricity imports actually diversify its energy mix6 and reduce supply shock exposure to natural gas, the fuel source for nearly 70 percent of its electricity.

Social and environmental impacts

While these drivers present a compelling case for hydropower development, and power trading more broadly, infrastructure projects and relocation raise significant social and environmental effects that must be addressed. These effects are specific to the infrastructure design and at least partially can be mitigated through appropriate pre-implementation design. Since power trading in the GMS has thus far been hydropower-based, we focus on the most common impacts associated with hydropower infrastructure. However, universal to all major projects is the central theme of cost-benefit mismatch. Some constituencies will reap windfalls at the expense of the most vulnerable when governance safeguards are weak or compromised.

On the social side, riparian communities from areas to be inundated are most affected. There is no guarantee the project wins their free, prior and informed consent, and they may possess few legal tools to ensure their rights, if any, are protected. Their relocation may result in the loss of ancestral lands and a shift to potentially less fertile areas where traditional livelihoods and agricultural practices are unsuitable. Existing development proposals may result in some Cambodian households being relocated for the second or third time in just 15 years.7 Accompanying the economic impacts such dislocation creates in the absence of compensatory mechanisms are social and psychological stressors. Added health risks may arise if resettlement areas lack clean water and sanitation access, resulting in infectious disease outbreaks.

Downstream communities are also severely impacted. Changes in river dynamics and water chemistry affect fisheries productivity with potentially adverse effects to protein availability and income generation from catch. Susceptibility to new disease vector dynamics may be another concern, such as greater malarial risks because of expanded mosquito breeding habitat. Downstream farming communities will be affected by changes in irrigation availability and timing, which could reduce agricultural productivity and prompt reliance on other water sources.

Environmental impacts are also multi-faceted due to ecosystem complexity, whereby imbalances in plankton populations alone can be enough to modify the river's biogeochemistry and predator-prey dynamics. Both flora and fauna species losses typically occur and endangered species native to the area may be at risk.8 Sedimentation loads will exert longer-term effects on ecosystem equilibrium and are compounded by landslides and siltation discharge from human activities in riparian areas. Less often discussed, but potentially significant, are the methane emissions from reservoir-based micro-organisms and other greenhouse gas emissions released from rotting vegetation.

Power trade as pro-poor intervention

Is it possible for negative impacts such as these to be mitigated and for benefits to be harnessed"if there is any linkage with poverty, it is based on the premise that by promoting economic growth, poverty will be reduced."10 The authors add that impacts depend on "the prior policy environment, installed infrastructure and the specific focus of policy measures." They find the poor are rarely consulted on the specifics of energy trade agreements, as one might anticipate, and that consultations are limited to groups affected by the infrastructure project itself.

In some cases there are clear pro-poor benefits. Exporting countries may use the extra revenue to cross-subsidise local users, in both their connection fees and tariff schedules, though this depends on pre-existing policies or the passage of new resolutions accompanying the power trade agreement. For example, the Greater Mekong Subregion Northern Power Transmission Project, with support from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the South Korean government, will extend interest-free credit for 18,800 Laos households to access grid electricity for the first time.11

Complementarily, the addition of low-cost electricity production through cross-border trade can drive down domestic tariffs. The ADB anticipates that integrating Cambodia into a regional market encompassing Laos and Vietnam could reduce their electricity costs from diesel generation by two-thirds. In turn, affordable electricity can stimulate productivity gains by enabling the use of labour-saving machinery and equipment, like irrigation pumps, which can yield significant returns for the poor.

Another means of ensuring the poor benefit from power trading is by earmarking export revenues for social development projects, as has been implemented in Laos where schools, education, and healthcare access will be underwritten by electricity trade revenues. With such arrangements, policymakers will exercise discretion over whether such social development projects are targeted at communities affected by power trade projects (e.g., displaced in the construction of a dam) or the population at large.

Then there are the knock-on effects, some positive and others negative, of how gains in electricity access or economic growth are distributed across the population. These secondary effects stem from the industrial expansion induced by greater electricity access, through firms establishing new operations and existing firms entering new markets. This expansion may create job opportunities for the poor and enlarge the country's tax base which can be drawn on to fund social development projects.

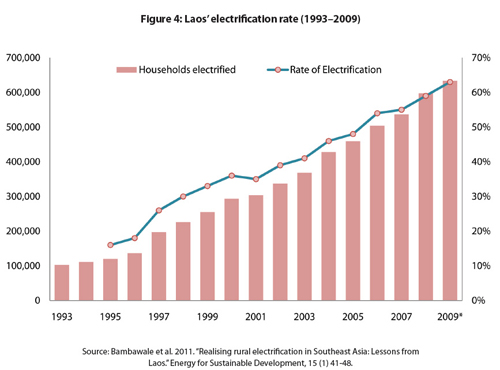

Governing the battery of Asia

Though Laos has engaged in power trading with Thailand since 1971 with the first Nam Ngum plant,12hydropower exports took on new dimensions of public visibility with the ground-breaking of the 1,070MW Nam Theun 2 (NT2) plant. NT2 is the country's largest completed project to date and the Laos government anticipates receiving more than US$2 billion from it over the 25-year concession period.13 A portion will be earmarked for social development and infrastructure construction, including electrification expansion in line with Electricite du Laos' targets of 80 percent of all households by 2015, and 90 percent by 2020.14

As Dr. Cruz-del Rosario notes in her interview, the NT2 project established the institutional environment and assessment requirements of future projects. Under the 2005 National Policy on Environmental and Social Sustainability of the Hydropower Sector in Laos, all hydropower projects exceeding 50MW in capacity and inundating more than 10,000 hectares are to execute both environmental and social impact assessments in full. Compliance consists of carrying out Environmental and Social Impact Assessments, Environmental Management Plans, Social Development Plans, Resettlement Action Plans, and Ethnic Minority Development Plans.

The governance mechanisms monitor long-term compliance with sustainability requirements and do not cease at project completion. In the case of NT2, an Environment and Social Panel of Experts annually visits the site area and identifies recommended and required changes to be implemented by the executing agency and other bodies.

Their most recent report cites concerns over the impact that unpoliced illegal logging and gold mining in the Nakai Nam Theun National Protected Area is causing, leading to siltation which will eventually compromise NT2's productivity and earned income. They also found that the deterrence mechanisms stopping illegal rosewood harvesting and wildlife poaching are currently weak, and that outsiders (non-resettled families) are chiefly responsible for the area's resource exploitation.

These observations reveal the long-term challenges associated with hydropower plans and resettlement, and the difficulties balancing current livelihoods needs against sustainable natural resource management. Towards that end, follow-up funding from the World Bank has been secured through the Laos Environment and Social Project. The project will further strengthen the country's institutional capacity to ensure the sustainable use of Laos' natural resources in a manner that generates both social and environmental benefits.

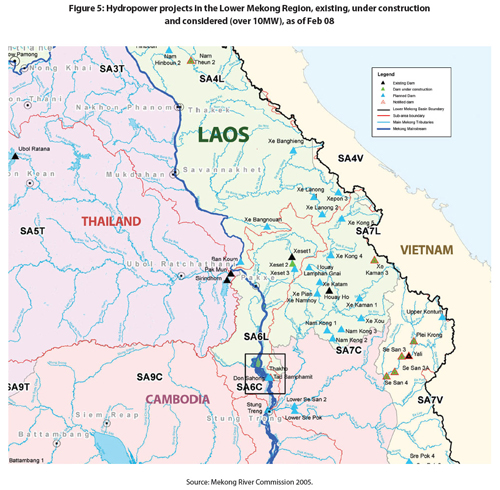

Around the corner

Laos has already signed Memoranda of Understanding with Thailand that supports the development of more than 7,000MW of power capacity for trading, and another 5,000MW with Vietnam. Combined, that is more than ten times the capacity of NT2, indicating strong growth expectations in the sector. According to an October 2010 report commissioned by the Mekong River Commission, Laos could receive US$2.6 billion per year if the 12 mainstream projects proposed for development on the Mekong come to fruition.15

Since NT2's commercial operations only began in March 2010, it is too early to tell whether its revenues will be properly managed and disbursed. If so, then revenue from the several thousand megawatts of plans already receiving Project Development Agreements could dramatically alter the Laos economy and people's access to education, healthcare, and transport infrastructure. But proper management is not a foregone conclusion, especially if the multilateral development banks whose stricter governance requirements are replaced with private equity firms with less interest in social and environmental protection.

The pace of development remains an ongoing cross-country discussion. Leaders of the four Lower Mekong Basin pledged sub-regional consultation and cooperation on riparian development through the 1995 Mekong Agreement, which saw its first-time activation late last year when Laos announced its proposal for the 1,260MW Xayaburi plant. As with previous projects, civil society groups have coalesced in opposition, with 263 groups signing a joint call to regional leaders to cancel the project.16

While the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand has already agreed to purchase electricity from the plant, which would not see completion until 2019, Cambodian and Vietnamese groups have voiced concern over downstream impacts and proposed postponing decisions on project development for another decade.

Postponement would not only allow scientists to better determine the long-term impacts of hydropower construction, but would also postpone the receipt of revenues that could help the 27 percent of Laotians living on less than US$1 a day climb out of poverty. Ultimately, the current state of power trading entails high-stakes decisions with at least one party losing out, either directly or in the form of lost opportunities.

This Energy Security section greatly benefited from the insights of Beni Suryadi (ASEAN Centre for Energy) and K. Witoon (Mekong Energy and Ecology Network).

This article was reproduced with permission from theb Asian Trends Monitoring Bulletin,Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy,National University of Singapore.For the full report, published 24 May 2011, click here.

By : Dr Benjamin K. Sovacool and Anthony D’Agostino, Asian Trends Monitoring Bulletin