By Ng Il Shan

Forecasting is always a tricky task.

“There are probably more jokes about forecasters than about lawyers,” quipped Mr Tony Wood, Energy Program Director of Grattan Institute, during the first session of SIEW Energy Insights.

When asked what sets DNV GL’s forecast of energy trends apart from the rest, Mr Ditlev Engel, CEO of DNV GL - Energy, explained that their forecast was based on objective dollars and cents, and not on “wishful thinking”.

DNV GL’s economic models revealed three global themes.

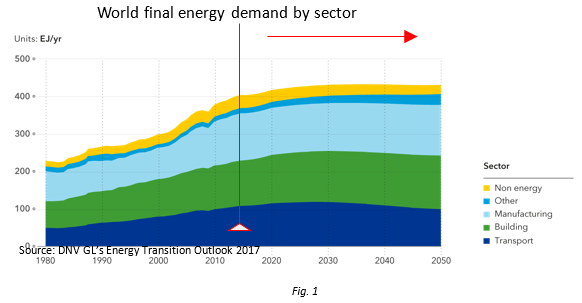

First, world final energy demand will plateau around 2030, at a level 7 percent higher than in 2015 (Fig. 1). This is due mainly to the models’ expectation that efficiency in energy use will continue to outpace GDP growth.

Second, world electricity demand will increase by 140 percent between 2015 and 2050, becoming the largest energy carrier for end-users. This increase is driven mostly by the rapid electrification of developing countries.

Third, renewables will account for 85 percent of world electricity production in 2050, with 36 percent of production attributable to solar PV, 24 percent to onshore wind, and 12 percent to offshore wind.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of this forecast is the massive growth of solar and wind energy from virtually zero contribution in 2015 to a generation potential of about 70 EJ/year each in 2050.

Other key findings include the increase in market share of electric vehicles in all major regions to 100 percent by 2050, and the decrease in global energy expenditure as a fraction of global GDP from 5 percent in 2015 to slightly above 2 percent in 2050.

Closer to home in Southeast Asia, energy demand is also expected to plateau – albeit later in 2040. Electricity generation increases much faster than in the global case, with solar PV and wind growing strongly to account for two-thirds of electricity generation in 2040.

A worrying trend for the region is the rapid reduction in coal exports to almost zero by 2050, accompanied by a corresponding increase in oil imports, said Mr Engel. This might pose challenges to energy security as Southeast Asia becomes more dependent on imported energy.

Mr Engel added that “unbridled” growth in solar PVs in the later years could also pose a challenge. For as long as solar energy relies on subsidies, governments may control the rate of its growth, he said. However, once solar energy is cheap enough to become competitive independently of subsidies, governments lose this lever, and homeowners may begin installing PV cells faster than the electricity network can accommodate them.